In this article

Introduction: The Beautiful Lie of “White”

“White wedding dress.” The phrase rolls off the tongue so naturally that nobody stops to question it. From glossy bridal magazines to global royal weddings, we nod along when a gown is called “pure white.” But is it, really? Or is it one of those cultural fibs we’ve all politely agreed upon — like saying you “just popped in for one drink” at the pub?

The truth is: most so-called white wedding dresses are anything but. They’re ivory, cream, champagne, oyster, ecru — and sometimes just cleverly lit polyester. To understand why we persist in calling them white, we need to take a tour through physics, perception, fashion history, and cultural mythology. Strap in: this is science class with a veil on.

The Physics of “White” in Wedding Dresses

Light behaves like a diva — it never simply arrives, it performs. When it hits the surface of a wedding dress, it doesn’t just bounce off politely; it refracts, scatters, diffuses and interferes with itself in ways that would make even the best hair stylist jealous.

Let’s break down what’s actually happening before our eyes — and lenses.

Light meets fabric: refraction and reflection

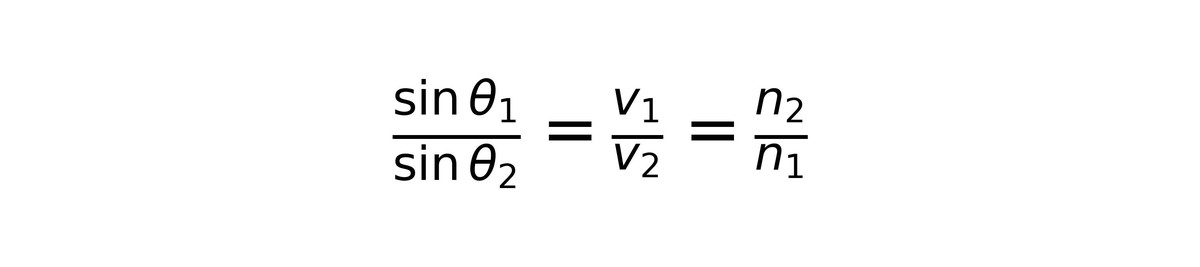

When light moves from air into another medium — like silk, tulle, satin, or lace — it bends. This bending is described by Snell’s Law:

Here n₁ and n₂ are the refractive indices of the two media (air and fabric), and θ₁ and θ₂ are the angles of incidence and refraction. The refractive index n is defined as the ratio of the speed of light in vacuum to its speed in the medium (v = c/n).

This means Snell’s Law can also be expressed in terms of light velocities: sin θ₁ / sin θ₂ = v₁ / v₂ = n₂ / n₁,

where v₁ and v₂ represent the speed of light in air and in fabric, respectively.

In practice? Light slows down when it enters denser material, changing direction. Some of it reflects back (which gives us the surface sheen of silk), and some penetrates deeper, bouncing between microfibres before escaping. That’s why satin gleams while chiffon glows — they’re literally sending light on different paths.

Think of every thread as a tiny prism, slightly redirecting the incoming light. The smoother the weave, the stronger the mirror-like reflection; the fuzzier or more irregular the surface, the softer the diffused look.

That’s also why the same dress can look radiant white under daylight, but creamy in candlelight: the refractive index (n) changes subtly with wavelength, a phenomenon known as dispersion.

Scattering: when light gets chaotic

Not all light behaves neatly. Some gets scattered in all directions — especially in materials with microscopic irregularities (fibres, threads, dust, even moisture in the fabric).

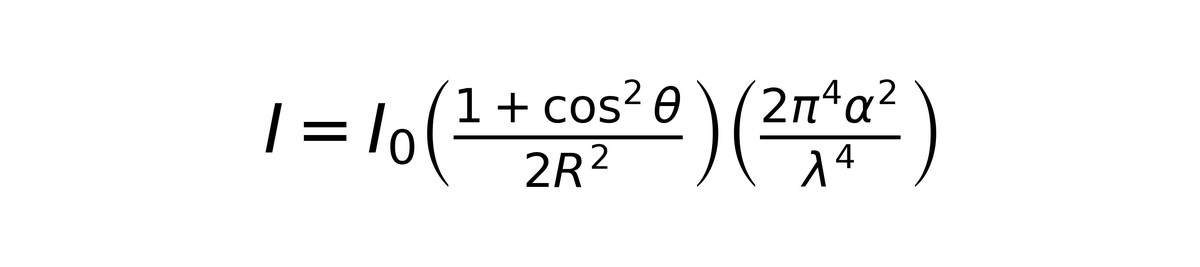

This is where Rayleigh scattering comes in, the same effect that makes the sky blue. Its intensity is inversely proportional to the fourth power of wavelength:

In this full form of Rayleigh’s equation,

I represents the intensity of scattered light,

I₀ is the intensity of incident light,

λ is the wavelength,

α the molecular polarisability,

R the distance from the scattering point,

and θ the scattering angle.

Shorter wavelengths (blue light) scatter more than longer (red), so depending on the fabric structure, the “white” dress might appear cooler or warmer. Under studio flash (rich in blue light), the dress may lean icy-white; under a sunset, the same gown turns golden.

This is why photographers constantly adjust white balance: we’re essentially negotiating with physics on behalf of the bride.

Absorption and Multiple Reflection

Once light has entered the fabric, the real party begins. It doesn’t simply reflect once and leave politely — no, it bounces, scatters, tunnels between fibres, and slowly loses energy along the way. This endless ricochet of photons inside a fabric is what gives materials their softness, depth, and that ethereal “glow” we associate with bridal gowns.

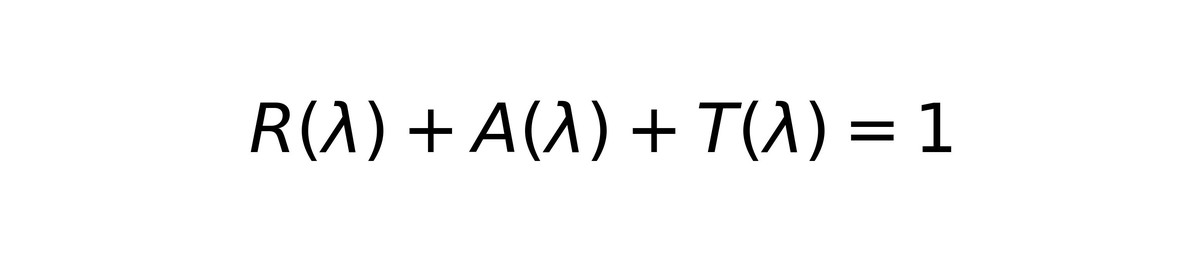

In optical physics, this process is described by a simple but elegant energy balance equation:

Where:

R is reflectance — the fraction of light that bounces back from the surface;

A is absorbance — the fraction absorbed and converted into heat (yes, technically your wedding dress warms up ever so slightly under sunlight);

T is transmittance — the fraction that passes straight through the material.

Together, they must always add up to 1 — meaning that every single photon is accounted for. Light can only do three things: bounce off, sneak through, or get eaten.

For wedding fabrics, the goal is to maximise R (the reflected part) and minimise A (the absorbed part), so the dress looks radiant rather than dull. But since no material reflects all wavelengths equally, there’s always a slight imbalance in the spectral response — and that imbalance creates colour.

If a fabric reflects less blue light than red, the result is a warmer tone — ivory, cream, champagne. If it reflects more blue than red, the tone shifts cooler — pearl or “optical white.”

Let’s compare a few examples:

Glossy satin acts like a mirror: high R, low T, moderate A. It reflects light directionally, creating sharp highlights — that liquid shimmer brides love.

Soft chiffon lets light diffuse through: moderate R, low A, high T. The result is airy, translucent elegance.

Matte cotton? Low R, high A, near-zero T. It absorbs more than it gives back, which is why you’ll never see a cotton wedding dress on a royal balcony.

Now add multiple layers — linings, tulles, lace overlays — and the internal reflections multiply. Each boundary between layers becomes a mini mirror, bouncing light back and forth before it finally escapes. This is why a well-layered gown almost seems to glow from within: you’re seeing the cumulative echo of thousands of micro-reflections, not some divine aura (though it’s flattering to think so).

So yes — when the bride “lights up the room,” physics is quite literally lending a hand.

The optical illusion of “optical white”

Just when you think you’ve got physics figured out, chemistry crashes the party. Many fabrics marketed as “optical white” aren’t naturally white at all — they’re treated with optical brightening agents (OBAs), microscopic dyes that fluoresce under UV light.

They absorb ultraviolet radiation (invisible to the human eye) and re-emit it as visible blue light, tricking our brains into seeing a brighter, “cooler” white.

Under daylight or camera flash — both rich in UV — these agents work overtime, making the gown sparkle like it just fell from heaven. But under tungsten bulbs or candlelight, where UV is minimal, that same “optical white” turns dull or even yellowish.

In other words: optical white isn’t a colour, it’s a chemical illusion. A bit like saying your teeth are whiter because your toothpaste glows in club lighting — technically true, socially hilarious.

For photographers, this creates a familiar headache: a dress can look perfectly balanced in one lighting condition and completely off in another. You can correct exposure, but you can’t outsmart fluorescence.

In short: “white” is just organised chaos

What we perceive as “white” is the sum of countless photon misbehaviours: refraction, scattering, absorption, re-emission, and occasionally, fluorescent showing off. Each fibre of a wedding dress is a chaotic playground where light goes in, panics, bounces a few times, and eventually emerges pretending to be pure.

So when we say a dress is “white,” what we really mean is: “enough wavelengths survived the chaos together that our brain gave up and called it unity.”

Why Our Eyes (and Brains) Insist on White

Light might be physics, but seeing is psychology — and your eyes are far less objective than you think. What we call “white” is less a wavelength and more a well-rehearsed hallucination performed by the brain to keep the world visually stable.

The stubborn illusion of colour constancy

If you’ve ever wondered why a wedding dress looks white in a church, on a dance floor, and even under neon bar lights — thank Edwin Land, the founder of Polaroid and the father of the Retinex theory. According to Land, our brains don’t measure colour directly. They compare it with surrounding colours and light levels, constantly recalibrating to maintain what’s called colour constancy.

In other words, your visual cortex is a living white-balance system. When the lighting turns yellow, your brain quietly shifts everything towards blue. When the scene goes cool and bluish, it adds warmth. The result? The dress stays “white,” even when physics insists otherwise.

It’s the same reason half the internet once saw The Dress as blue and black, and the other half swore it was white and gold. There’s no trick — just millions of brains disagreeing on which colour-correction preset to use.

Weber–Fechner and the illusion of brightness

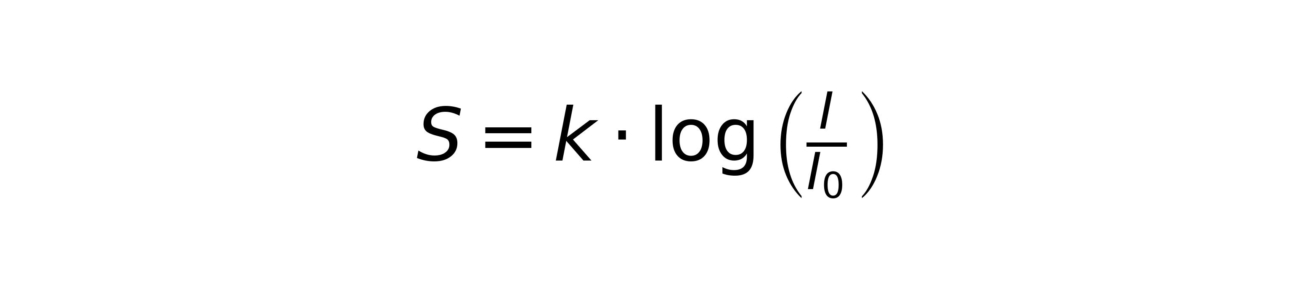

Now, let’s talk intensity. Even if you doubled the amount of light hitting a dress, it wouldn’t look twice as bright. Why? Because human perception follows a logarithmic scale described by the Weber–Fechner law:

Where:

S is the perceived sensation (brightness),

I is the physical intensity of light,

I₀ is the threshold intensity (the smallest detectable difference),

k is a constant specific to human perception.

This means small variations in luminance between different fabrics — ivory, champagne, or optical white — are often below the threshold our brains care about. To us, they collapse into the same general category: white enough.

So when your aunt says “it’s pure white,” she’s not wrong. She’s just working with a logarithmic eyeball.

Hering’s truce: when the brain stops arguing

At the end of the 19th century, Ewald Hering proposed the opponent-process theory of colour vision. According to it, our visual system encodes colour using three opposing pairs:

- red vs. green,

- blue vs. yellow,

- black vs. white.

When none of these channels dominates, the result is perceived neutrality — white or grey. So technically, white isn’t a colour; it’s a peace treaty between your neurons.

“White,” said no physicist ever, “is simply the brain giving up and calling a truce.”

Mach bands and the local drama of contrast

Our brains exaggerate edges. The Mach band effect, named after physicist Ernst Mach, makes bright regions next to dark areas appear even brighter. In wedding photography, this happens all the time: a white gown against a dark suit looks dazzlingly luminous — not because it is, but because your visual cortex cranks up the contrast to detect boundaries more clearly.

That’s why brides often seem to “glow” beside their partners. (Physics provides the photons, but psychology adds the halo.)

Chromatic adaptation — the eye’s built-in white balance

Stare at a yellowish scene long enough and suddenly everything looks cooler once you step outside. This is chromatic adaptation, the biological version of Lightroom’s temperature slider. Your cone cells adjust their sensitivity over time to neutralise dominant colours in the environment. That’s why candlelight, sunlight, or LED strips all make the same dress appear white — each lighting condition triggers a different internal calibration.

It’s also why photographers spend their lives chasing “correct” white balance, while the human brain does it flawlessly in real time — and for free.

So why do we keep falling for it?

Because “white” is comfort. It’s stability. It’s the brain’s way of saying: I’ve got this under control. Our visual system evolved to ignore lighting changes, not to measure spectral truth. So even if the light bouncing off a wedding dress is physically tinted ivory, our brains restore the status quo — the colour of ritual, purity, and social expectation.

In short: physics defines the wavelengths, but perception writes the story.

And in that story, white isn’t just a colour — it’s a collective act of imagination we’ve all agreed to share.

From Queen Victoria to Meghan Markle: A Not-So-White History

If white wedding dresses had a royal godmother, her name would be Queen Victoria. When she married Prince Albert in 1840 wearing a white silk satin gown trimmed with Honiton lace, she didn’t invent the colour choice — she simply made it go viral (in the 19th-century sense of the word).

Before Victoria, brides of means occasionally wore pale dresses, but colour was the norm. Blue symbolised fidelity, gold meant prosperity, and rich fabrics in burgundy or silver were the height of taste. White was a terrible practical choice — it stained easily, cost a fortune to clean, and only the wealthy could afford to wear it once. Which, of course, made it perfect for royalty.

In the 1840s, white wasn’t innocent — it was expensive.

What made Victoria’s dress legendary wasn’t just the gown itself, but its reproduction. Britain already had a thriving press, and the young queen’s wedding became one of the first royal events mass-distributed through engravings and illustrated newspapers. The Illustrated London News would launch just two years later, continuing to reprint the image for decades. There were no wedding photos — daguerreotypes had only just been invented — but the engravings did the job beautifully.

It was print, not photography, that first turned “white wedding” into cultural shorthand. (Ironically, photography later kept the myth alive — white photographed better than anything else on early film stock, which adored contrast.)

The Victorian Class Code

For Victorian society, white soon became a social signal as much as a fashion statement. The industrial revolution had created a middle class hungry for status — and the “white wedding” offered a chance to imitate the queen. Wearing white said, I can afford to be impractical. It was the 19th-century equivalent of posting your honeymoon on Instagram.

Working-class brides, meanwhile, often wore brown or grey dresses — colours that could be reused for Sunday best. Their weddings were no less sincere, just less photogenic by upper-class standards.

Hollywood, Royalty, and the Century of Reinvention

Fast-forward a hundred years, and the idea of the “white wedding” exploded again — this time through the lens of mass media. Hollywood crowned its own bridal icons: Grace Kelly’s satin-and-lace masterpiece in 1956, Audrey Hepburn’s short Balmain dress, and the fairy-tale extravagance of Princess Diana’s 1981 gown with its 25-foot train. Each of these moments reinforced the mythology: the bigger the spectacle, the whiter the story.

And yet, none of those famous gowns were truly white.

- Grace Kelly’s was antique ivory.

- Diana’s was ivory silk taffeta.

- Kate Middleton’s McQueen dress? Ivory satin gazar.

- Meghan Markle’s Givenchy? Soft ivory silk.

Still, every headline called them “white.” Because the narrative demanded it — the illusion of continuity from Victoria’s day to ours.

The Modern Meaning of White

Today’s brides inherit that legacy but rewrite its message. Designers like Vera Wang, Vivienne Westwood, and Stella McCartney use white not as a moral badge, but as a minimalist statement — a blank page rather than a purity test. “Bridal white” has splintered into an entire spectrum: ivory, pearl, champagne, ecru, eggshell, frost. Each shade tells its own story, none claiming absolute purity.

In much of the world, the symbolism flips entirely. In India, China, and Japan, white is traditionally the colour of mourning. Which, depending on your opinion of marriage, is either poetic or prophetic.

A Continuum, Not a Colour

From Queen Victoria’s lace to Meghan Markle’s silk, “white” has never meant a single hue — it’s a performance that changes with every era, every light, and every photograph. The meaning of white has travelled from wealth to virtue to style — and somehow, it still rules the altar.

Maybe that’s the real secret: white isn’t a colour we see, it’s a story we keep telling.

The Myth of White = Pure

By the mid-19th century, white had quietly traded its practical meaning for a moral one. What had started as a symbol of luxury — silk that only the wealthy could afford to ruin in a single day — became repackaged as an emblem of virtue. The transformation wasn’t about fabric; it was about social control disguised as fashion.

Victorian England adored the idea of purity. It was a convenient narrative for a society obsessed with propriety and gender roles. A white wedding dress became the ultimate public declaration of innocence — the kind that was expected of women, but never demanded of men. The irony could fill a cathedral.

White wasn’t about innocence — it was about obedience wrapped in lace.

The link between colour and morality wasn’t ancient at all. In medieval Europe, brides wore red, blue, green — whatever showed status and taste. “White = pure” only took hold when Christian moralism met industrial capitalism. As the 19th century marched on, the symbolism of purity turned into an industry: lace, linens, soap, starch — all advertised in white, all promising a cleaner, holier life.

Anthropologist Mary Douglas once argued that purity is not about cleanliness, but about order. It’s a way of saying “this belongs here, and that doesn’t.” In that sense, the white wedding dress wasn’t about moral superiority — it was about tidying up womanhood.

The commercial resurrection of purity

Fast forward to the 20th century, and the purity myth was reborn — this time under studio lights. The post-war boom turned weddings into theatre, and the bridal industry realised that innocence sells. Glossy magazines, Hollywood films and department stores wrapped “purity” in organza and sold it by the metre.

By the 1950s, the “white wedding” was no longer a symbol of virginity, but of aspirational perfection — suburban, photogenic, economically stable. You could be divorced, remarried, or far from innocent; as long as you wore white, you played your part in the collective daydream.

The purity myth turned out to be brilliant marketing — easy to print, easy to sell, impossible to verify.

White has ruled the bridal palette for nearly two centuries, but colour never really left — it just hid in plain sight. For a brighter (and cheekier) look at what red, green and blue say about modern weddings, take a look at RGB Weddings – and Why White Isn’t Even a Colour.

The global irony

Across much of the world, white means something else entirely. In parts of Asia, it’s the colour of mourning. In African and Middle Eastern traditions, it’s often used for funerals or rituals of transition. In those cultures, white marks an ending, not a beginning — which, depending on your view of marriage, may be perfectly fitting.

In some cultures, wearing white to your wedding would be the fastest way to terrify your in-laws.

It’s a good reminder that colour symbolism is never universal; it’s just local storytelling in disguise.

Reinventing the meaning

Today, brides still choose white — but not out of moral duty. They choose it because it photographs beautifully, because it feels luminous, because it connects them to a tradition that has outgrown its sermon. Modern designers treat white not as purity, but as potential — a neutral canvas waiting to be personalised, layered, redefined.

Maybe that’s the quiet revolution: the only thing truly “pure” about the white wedding dress is how honestly it keeps reinventing itself.

Through the Lens of a Wedding Photographer

Every photographer knows the truth: there’s no such thing as white. There’s only the delicate dance between light, fabric, and human expectation — and every wedding is its own private experiment in how far physics can be persuaded to behave.

A dress that glows angelic under morning light can turn creamy in the afternoon sun and silver under the flash at midnight. Daylight leans blue; candles go gold; fairy lights whisper amber. Even LEDs — that modern plague of inconsistent colour temperature — add their own strange flavour. Each hue tells a slightly different story, and each one insists it’s the truth.

From behind the lens, I see it all shift in real time. When I photograph a bride walking down the aisle, I’m watching not just emotion, but light: how it bends, scatters, reflects. The same fabric that looked pearl in the mirror can appear champagne on camera, depending on the balance between Kelvin and chaos.

The camera’s sensor, poor thing, doesn’t know about cultural myths. It only records photons. So it captures what’s really there — the texture, the warmth, the imperfections that human vision politely edits out.

Physics bends the light; the brain straightens the story; the camera just keeps the evidence.

That’s where documentary wedding photography becomes something more than reportage. It’s the act of choosing which truth to show: the optical one or the emotional one. And often, they’re not the same.

Every so often, a bride asks me if her dress will look white in the photos. I always give the same answer: “Yes — and also no.”

Because it will. It will look white to her, to her family, to everyone who remembers how she looked that day. But the pixels will tell a different story — one of warm light, mixed shades, imperfect reflections. And that’s fine. Perfection is sterile; honesty has texture.

A wedding dress never lies, but light does — sometimes kindly, sometimes cruelly.

There’s a strange comfort in that. I’ve learned to stop chasing absolute white. It doesn’t exist — not in physics, not in fabric, not in feeling. What matters is how the light falls when no one’s posing.

That’s the heart of documentary wedding photography: no filters, no faking, no pretending that “white” is ever just one thing. It’s everything at once — all the colours playing nicely together for half a second before scattering into memory.

White isn’t the absence of colour; it’s every colour, waiting to be seen. That’s why we keep photographing it.

Conclusion: The Most Colourful Non-Colour

After all the theories, physics, fabrics and myths, perhaps the only thing truly constant about white is how much it refuses to stay still. It bends to light, to culture, to perception — and still manages to convince us it’s pure, stable, eternal.

Every “white” dress is a collaboration: between photons and fibres, tradition and imagination, camera and memory. It doesn’t represent perfection; it reflects adaptation.

White isn’t the absence of colour — it’s every colour, briefly agreeing to coexist.

And maybe that’s why we still fall for it — because for one fleeting moment, under all that light and lace, illusion and reality finally look the same.